A Lesson in Irrational Decisions

Somewhere between a blackout and a heatwave, I convinced myself that buying a bread maker was the solution to all my problems.

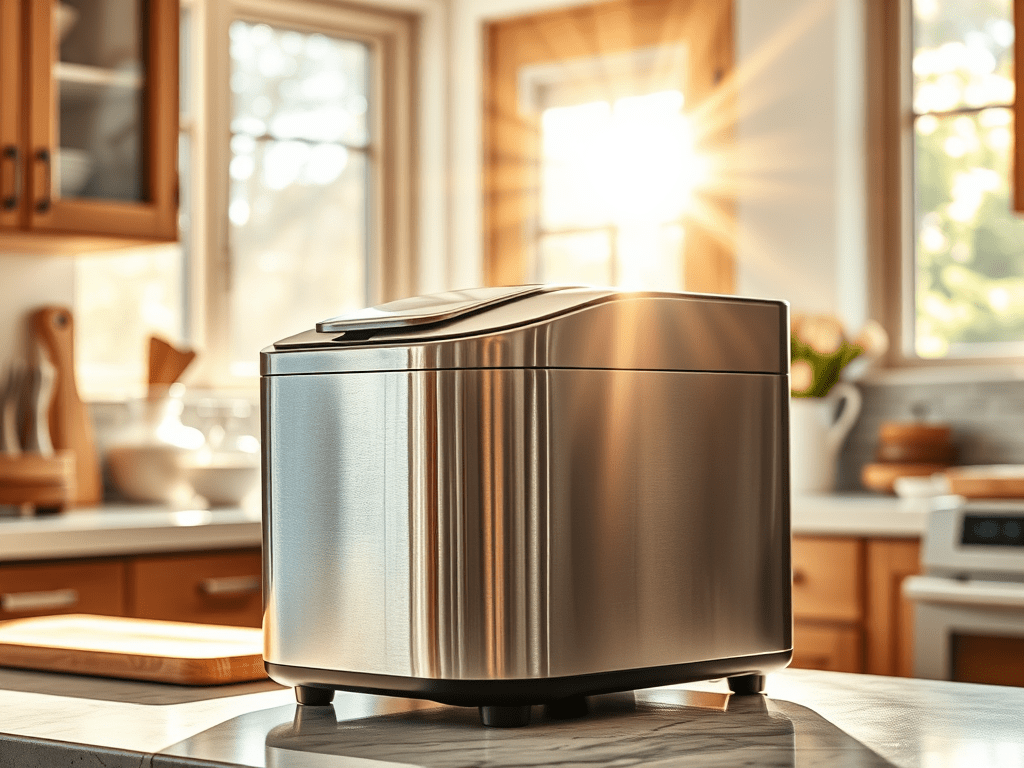

I was sweating through a sleepless night, scrolling Pinterest, and there it was: a sleek stainless-steel machine promising crusty loaves and rustic self-sufficiency.

Within minutes, I had paid more for it than I’d ever spent on any kitchen appliance. The next morning, I woke up to 38 degrees, no electricity, and a deep sense of regret.

At first, I brushed it off. It was a “treat yourself” moment. But looking back, it was a perfect example of how irrational our decision-making can be, especially when we’re stressed, overwhelmed, or emotionally overloaded.

Let’s break it down.

The illusion of rationality

We like to believe that our decisions are logical. That we take in information, compare options, and choose the best possible outcome based on reason.

This is the assumption behind the classical rational model of decision-making, outlined in Buchanan and Huczynski (2019, p. 682).

In theory, I should have considered the climate, the power cuts, my actual baking habits, and the cost-benefit ratio.

Instead, I imagined myself in a linen apron, tearing open a sourdough loaf on a wooden board like one of those effortless Parisian homemakers on Instagram.

In reality, decision-making is rarely that clinical. It is often shaped by limited time, limited information, and the internal emotional state of the decision-maker.

This is what Herbert Simon called bounded rationality — the idea that we make “good enough” decisions rather than optimal ones, because our capacity to process information is finite (Buchanan and Huczynski, 2019, p. 683).

What was really driving my decision?

In hindsight, the purchase wasn’t about bread. It was about control. I was feeling burned out, creatively blocked, and stuck in a cycle of stress. Baking felt like a productive escape.

A way to create something beautiful and tangible. This is where the descriptive model of decision-making offers more insight.

It recognises that our choices are influenced by internal cognitive shortcuts, habits, emotional states, and social context.

We often operate on autopilot, guided by what feels urgent or comforting rather than what is objectively wise.

Instagram’s perfectly curated kitchen reels didn’t help either. I was bombarded by aesthetic content showing slow mornings, homemade brioche, and softly lit countertops.

This was a classic case of availability bias — a cognitive shortcut where our judgment is influenced by the most immediate examples that come to mind.

Because bread-making was everywhere in my feed, it felt like a widespread, achievable solution. As Buchanan and Huczynski (2019, p. 686) describe, availability bias can seriously distort how we assess risks, needs, and trends.

What I could have done differently

If I had followed a prescriptive model of decision-making, the outcome might have been very different.

These models guide us toward structured, reflective thinking to reduce bias. I might have paused to write down the pros and cons, or even just asked myself a few simple questions:

- Will I use this more than twice a year?

- Will it add stress or solve it?

- Can I achieve the same comfort in a less chaotic way?

Even basic reflection would have helped me realise that my decision was emotional, not strategic.

The emotional cost of irrational choices

In the end, the bread maker is still sitting in the corner of my kitchen, unopened. Every time I look at it, I feel a tiny stab of guilt — not just about the money, but about the fact that I acted on impulse rather than intention.

According to decision-making theory, irrational decisions often carry emotional consequences like regret, self-doubt, or anxiety, especially when they conflict with our values or circumstances.

But there is also a valuable lesson in this. Being human means making mistakes. Understanding why we make those mistakes can help us become more aware, more compassionate with ourselves, and better equipped next time.

I didn’t need sourdough. I needed rest. And no appliance, no matter how stylish, was ever going to give me that.

References

Buchanan, D. A., & Huczynski, A. A. (2019). Organisational Behaviour (9th ed.). Pearson.

Comment